A General History of Quadrupeds

1790

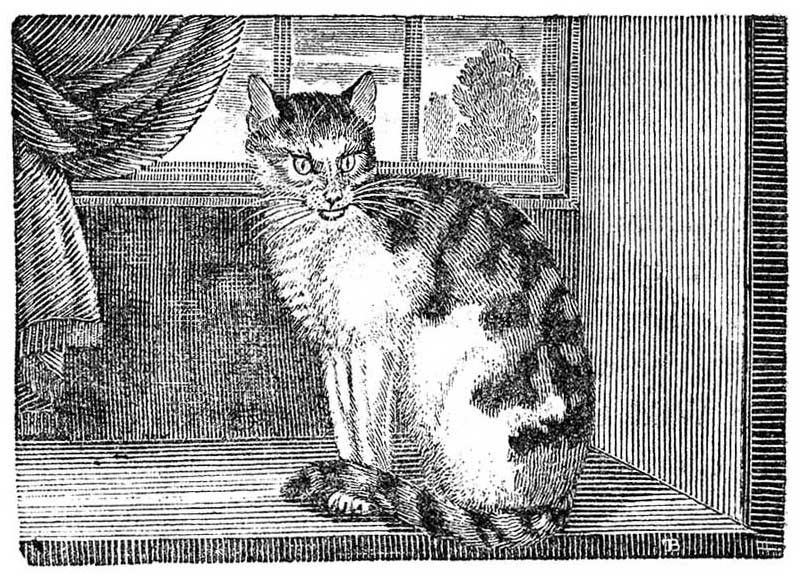

Domestic Cat, p. 192.

[From Thomas Bewick My Life, edited by Iain Bain, p. 124—5 (spelling and punctuation as given in the original manuscript)]

'Having from the time that I was a school boy, been displeased with most of the cuts in children’s books, and particularly with those of the “Three hundred Animals” the figures of which even at that time I thought I could depicture much better than those in that book [...] I at last came to the determination of commencing the attempt.[...] In this, my only reward besides, was the great pleasure I felt in imitating nature.[...] Such animals as I knew, I drew from memory upon the wood; others which I did not know, were copied from Dr Smellie’s abridgement of Buffon and from other naturalists, and also from the animals which were from time to time exhibited in shows. I made sketches, first from memory, and then corrected and finished the drawings upon the wood, from a second examination of the different subjects. I begun this business of cutting the blocks, with the figure of the Dromidary on the 15 of November 1785 (the day on which my father died). I then proceeded in copying such figures (as above named) as I did not hope to see alive.[...] The greater part of these wood cuts were drawn and engraved at nights, after the day’s work of the shop was over.'

Bewick’s first major independent publication was printed and published in 1790 in Newcastle upon Tyne. The single volume had been nine years in the preparation. It contains 199 figures illustrating brief descriptions of the animals, their habits and habitats. Most of the engraving was done in the evenings after a day's work in the workshop.

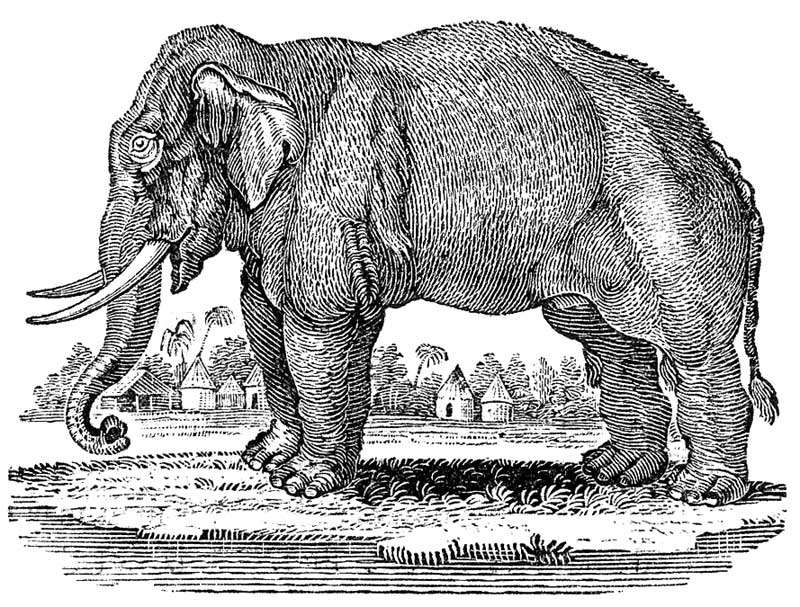

Some of the descriptions are short, say half a page, and others quite lengthy - the Elephant has 11 pages of text. There is room for argument about how much of the text was written by Bewick and how much by Ralph Beilby. The title page does not give details on the writing, mentioning only “the figures engraved on wood by T. Bewick.” Although some of the original drawings are still extant, they are mainly of the figures without the backgrounds, which were added directly to the woodblock in the process of engraving.

In addition to many purely ornamental vignettes designed as simple space fillers (and often repeated), there are also 39 illustrative vignettes used mainly as tailpieces, the first such appearing on p. 63, an image of a pack horse. Several of these feature human figures involved in activity almost amounting to a story. Bewick referred to these as his “tale-pieces”.

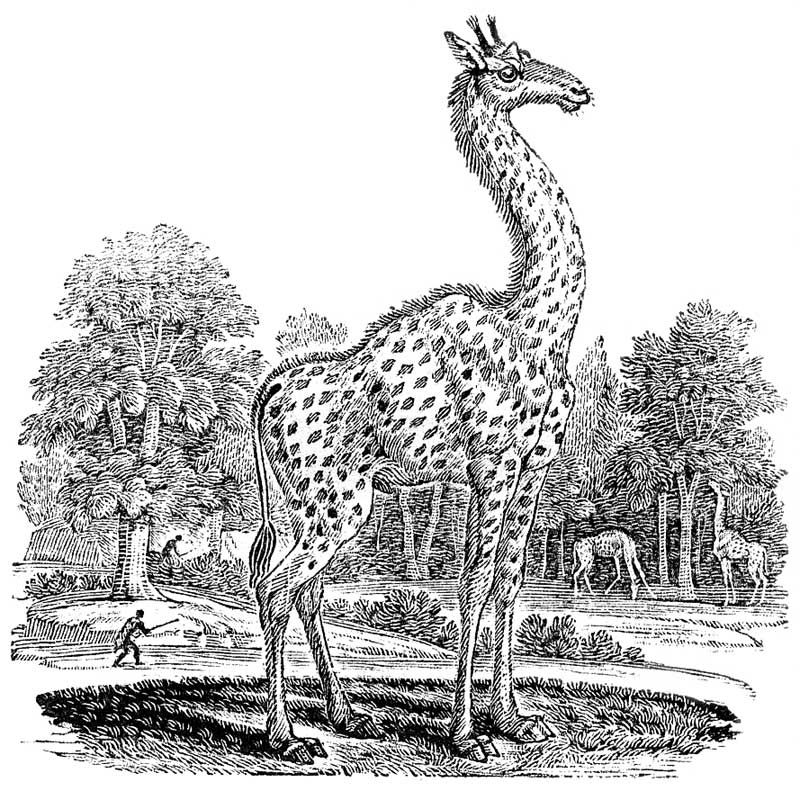

The Giraffe, or Cameleopard (page 91) It is not likely that Bewick had ever seen a real giraffe. The curvature of its neck in this image suggests a flexibility which is not quite possible, and the “large spots of yellow over the whole body” are actually far too small — too much like leopard’s spots — to be recognisable as typically giraffe to the modern eye, which has access to colour film and video representations. But the figure is only one element of the engraving. What was unusual to Bewick’s contemporaries, who had no better representation of a giraffe to compare it with, is the added detail of the background: the trees, the two small giraffes browsing in the copse, the two small human figures on the left. This imagined back–ground is the Bewick trademark. The engraving is an example of how Bewick, the artist above all of direct observation, could deal imaginatively with a subject he had no direct experience of.

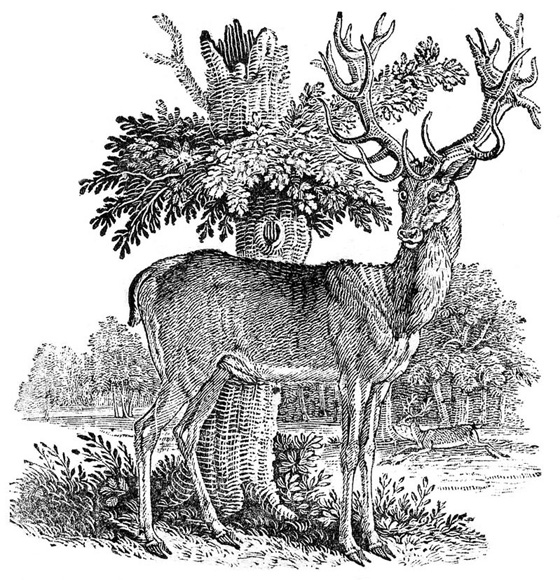

The Stag, or Red Deer (page 105) The stag is based on direct observation of and familiarity with the animal in its natural environment. The double background, of ruined oak tree with new growth sprouting just behind the figure, and the running stag and wood in the far background, would have been added directly to the wood during the engraving. It is interesting and inventive in two ways, compositionally and technically. The sprouting tree balances the wonderful antlers of the stag; the ruined oak coming back to life is a recognisably romantic trope. Technically it is noticeable that there are different levels of ink density, achieved by Bewick’s innovative layering of his cut on different levels, so that differing pressures could be achieved at one pull.

Elephant, p. 151.

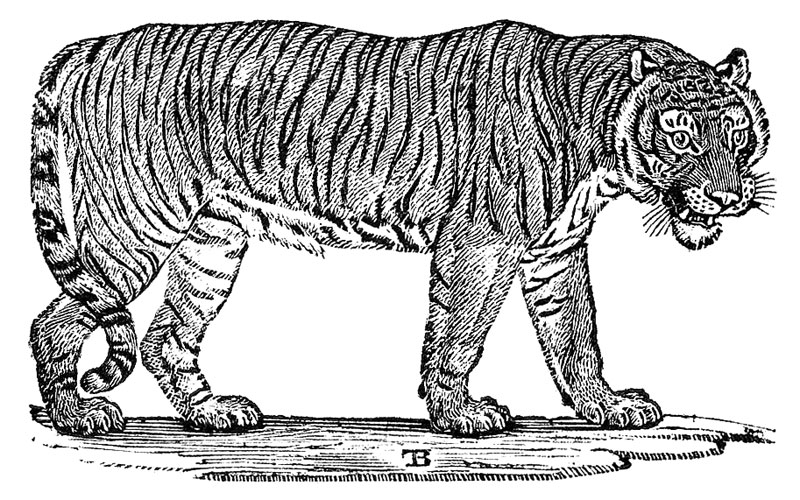

Tiger, p. 171.

Tiger, p. 171.

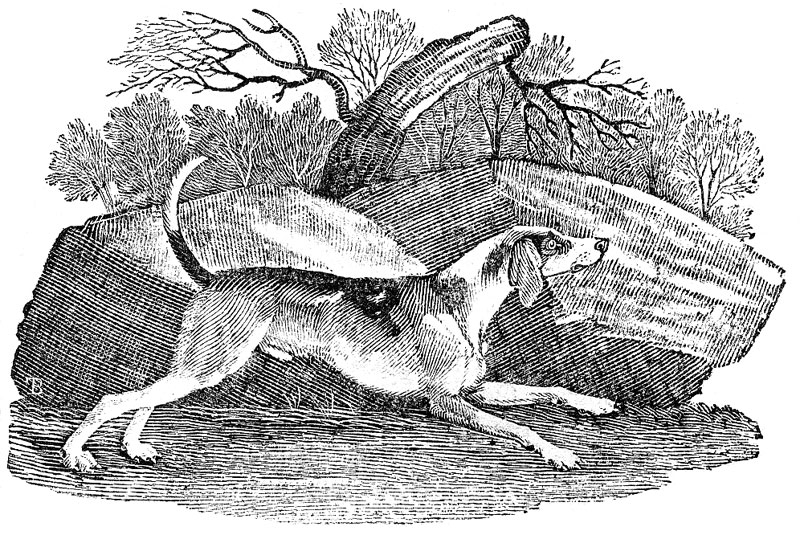

Fox Hound, p. 301.

Fox Hound, p. 301.